text

21.07.24 #007

Thinking about thinking

;; 2989w; 15'KEYWORDS: thinking, education, life

I want to talk about how I think. Or perhaps I should say, about how I think that I think. As usual, these are ideas I've had in my mind for a while, but that I never bothered trying to capture, write down, or formalize. Until now. I've not done any research on this topic, so it's very likely I'm just repeating something that someone else already noticed. Good for them. I don't really care.

This essay is structured in two parts. First, I will introduce a model for rational thinking, and try to map back and forth from this model to some concepts that you should already be familiar with. Then, I will try to justify why I even introduce such a model in the first place by showing how it can be applied for a variety of situations.

Let's get started.

Thinking as navigating a directed hypergraph

How do you perceive the act of thinking? If you had to explain it to somebody, if you had to describe what it is exactly that you do when you're thinking, how would you do it?

For me, it feels like solving a puzzle. I've a bunch of pieces, and I'm trying to make them fit with a specific purpose. Well, it turns out we can formalize this a bit if we try to express it in terms of graph theory, as the process of building and subsequently navigating a directed hypergraph.

We should start by defining our nodes and our edges. In the graphs we will be building, the nodes represent statements, propositions, truths, facts, and similar bearing entities. And the edges represent operations, properties, theorems, definitions, that directionally connect multiple nodes. I'm being deliberately vague here because I want to remain flexible, and also because I'm too lazy to be more precise. Some examples should help to understand what I mean.

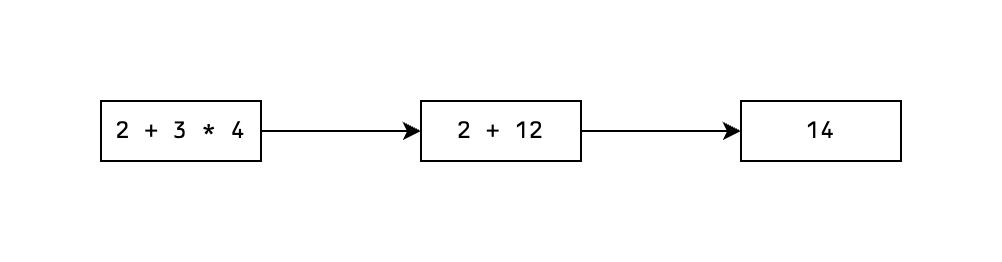

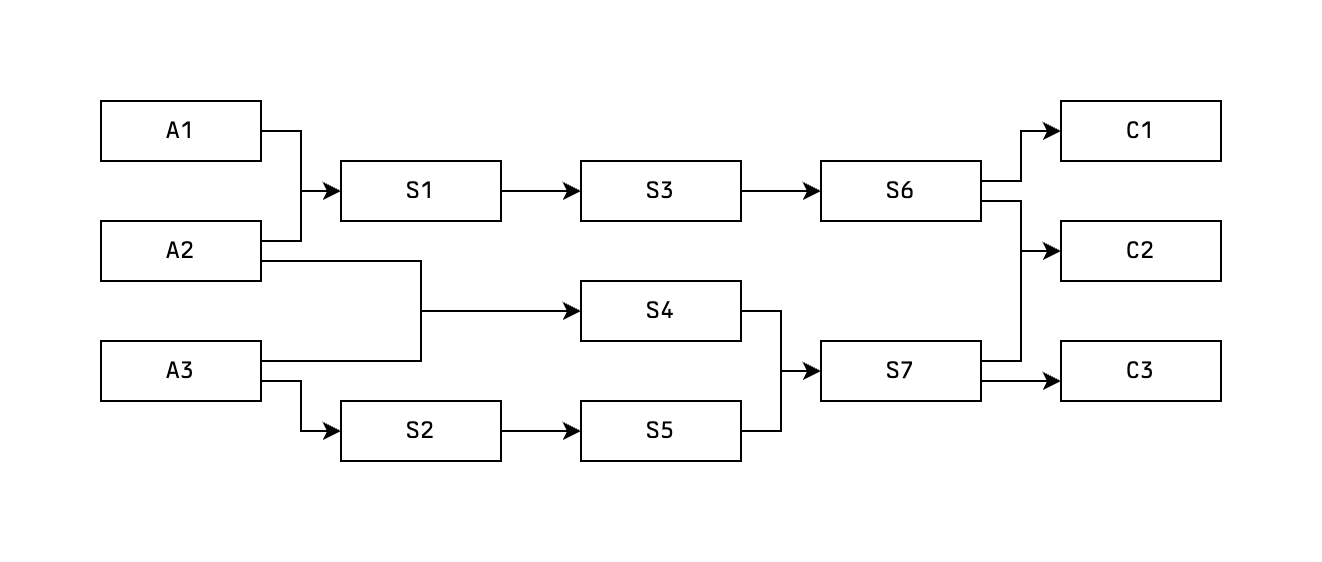

The first trivial example would be the following graph that represents evaluating a mathematical expression:

Here all the nodes are trivial bearing entities that represent the expressions or values themselves. And our directed edges represent the application of a given mathematical operator, which allow us to transform a given expression into a different but equivalent expression.

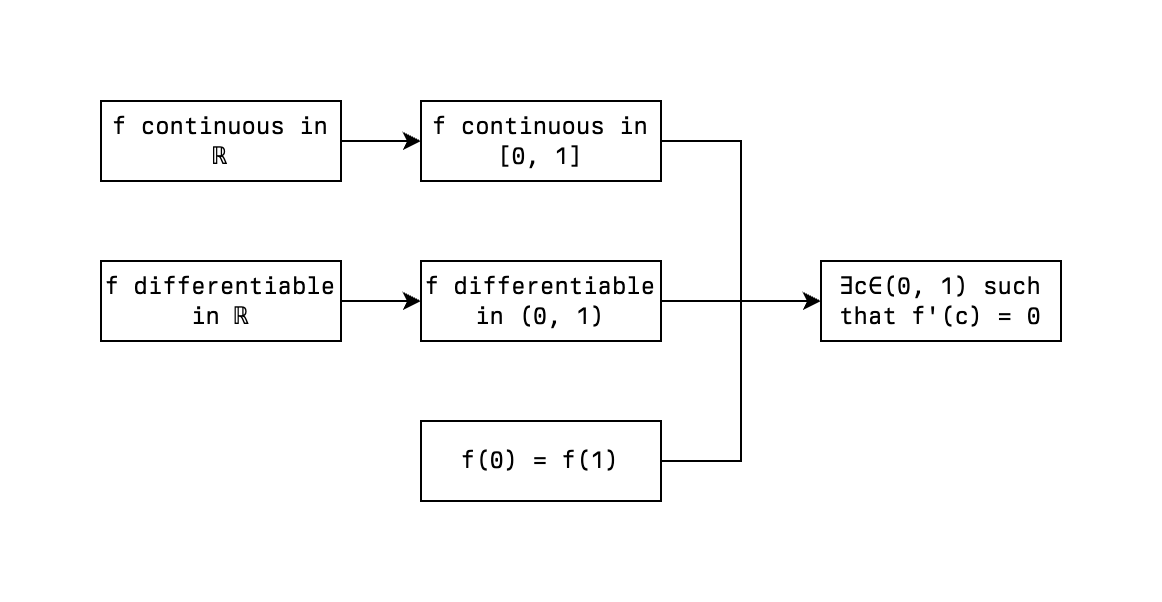

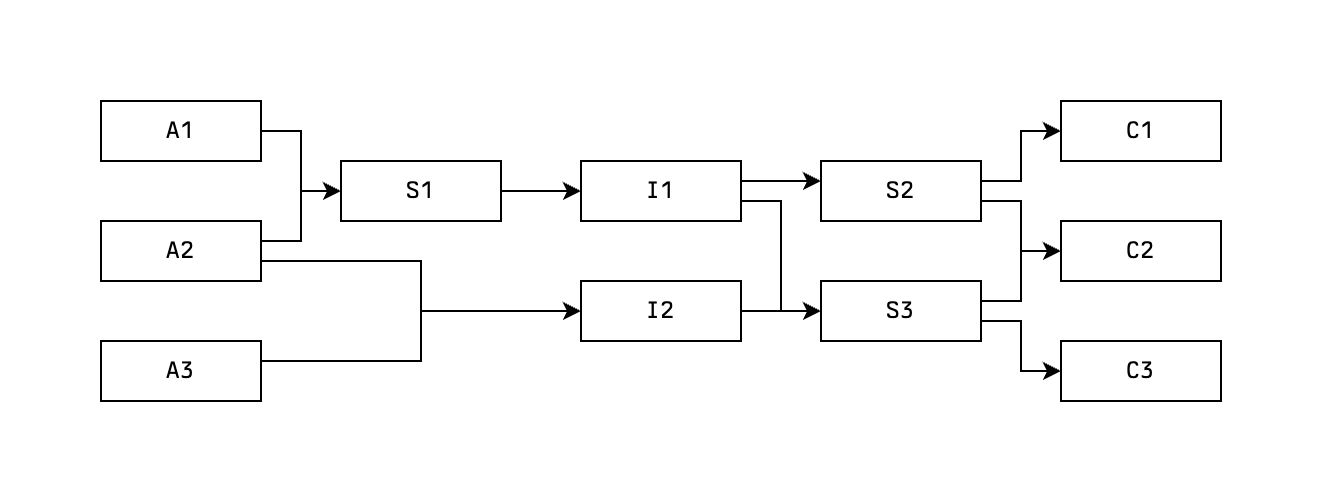

But this is just an uncool, plain-old graph. There's nothing hyper about it. Let's introduce the requirement of a hypergraph with a slightly more elaborate example:

We need a hypergraph to capture the requirement that some of our edges express a relation between multiple statements on one side, and potentially multiple statements on the other. This is nothing more than adding the capability to express logical conjunction to our model. And before you ask, logical disjunction is already trivially there. Can you see it? It's easier than you think, (A | B) -> C is equivalent to A -> C and B -> C. Easy.

I hope this is enough to paint the picture, because I don't want to do more examples. Rather, let's start thinking with it.

Because the thing is, for a given particular instance of thinking the hypergraph itself does not yet exist (in most cases). It's something that we need to build on the spot, as we think along.

To do so, we have a toolkit of edges at our disposal which we can constantly grow it by learning new shit, and how we build it will depend on the type of thinking we're trying to do. "What do you mean with 'type of thinking'?", I hear you ask. And I'm glad you did. I'll now define three distinct types of thinking, because I feel like it, and because it makes me sound smarter than I am.

Type A, or "Forward exploration"

In Type A thinking we start from a set of assumption statements and the goal is to start building the graph forwards to see to which new conclusion statements it leads us. Ideally, we have some kind of goal or direction in which we want to go. Something we're trying to achieve. But this could also be a purely exploratory exercise, which is why I've chosen to call it this way.

We've seen an example of this already: evaluating a mathematical expression. Here the goal is to operate on our single assumption statement that represents an initial expression, until we reach a statement that represents an equivalent expression which we consider to be "irreducible", whatever that means for us.

Type B, or "Backward exploration"

Unsurprisingly, in Type B thinking we start from a set of conclusion statements and the goal is to start building the graph backwards to see to which new assumption statements it leads us.

A typical example would be working backwards from a desired outcome such as moving to a different country. We start from the set of conclusion statements that represent our desired outcome, and we can work backwards until we have a list of assumption statements that we now need to go and fulfil, as well as a plan to achieve the desired outcome.

Before we move to the last type, I want to note that in both Type A and Type B, we are allowed to go in the "opposite" direction, if that is of interest. We are, after all exploring. But we are trying to move in one particular direction, relative to our set of starting statements. In Type A, we will want to "start" from them, which is why I've been calling them "assumptions", without bothering to define what this means. Similarly, in Type B we will want to "arrive" at them, which is why I've been calling them "conclusions", without bothering to define what this means.

Ok, lets move on.

Type C, or "Pathfinding"

We've seen what we can do with a set of assumption statements, and what we can do with a set of conclusion statements. So the obvious question is: What can we do if we have both? We can do Type C thinking.

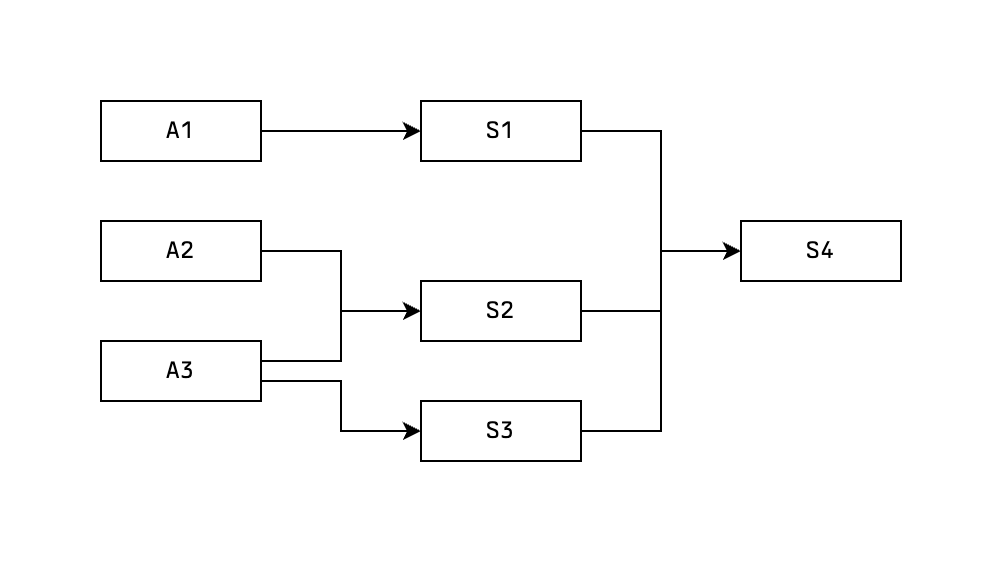

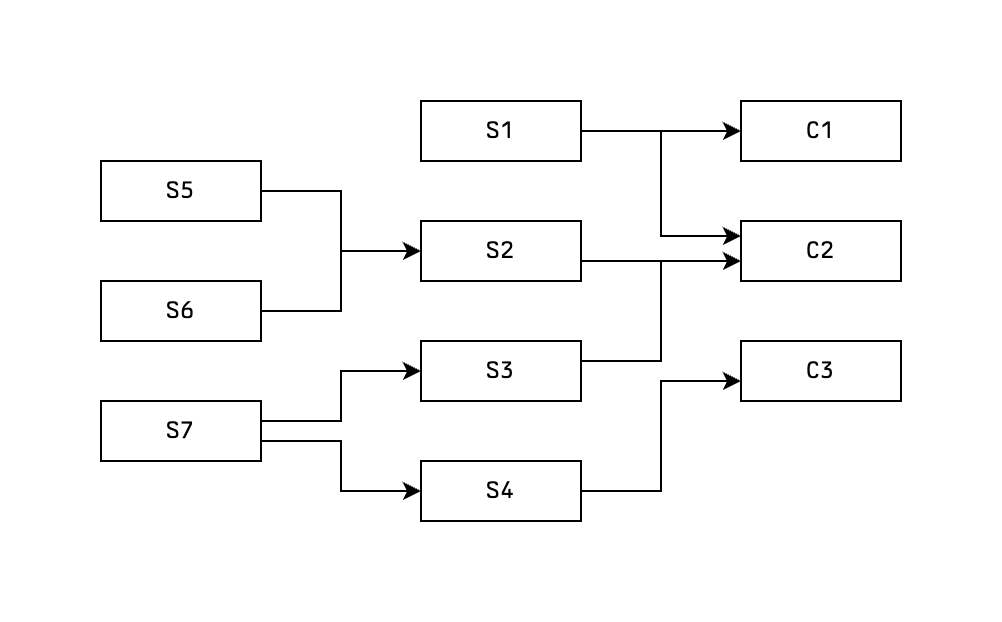

In Type C thinking we have both a set of assumption statements and a set of conclusion statements, and the goal is to start building the graph between them until we can build a path that connects them. Or is it? We can define two different subtypes for Type C thinking.

Subtype C+

The first subtype is where the goal is to build this path. Usually there's no prescribed way to proceed, we could choose to start from the assumption statements and work our way forwards Type A style, we could start from the conclusion statements and work our way backwards Type B style, or do both and aim at meeting somewhere in the middle. The precise choice will depend on the specific statements, and the edges available in our toolbox. Instinct/gut feeling plays a big role here. Sometimes you just know in which direction to start exploring. It's hard to describe. All I know is that I remember not having this ability, and then having it. All I did in between was just practice.

A common strategy, in which this instinct/gut feeling plays a facilitating role, is to identify good intermediate statements. Statements that are not trivially equivalent to the source or destination statements, but for which you have a very good confidence that you can build a path to either. So you might as well try to build a path from this intermediate state and see if the way to the other side becomes clearer.

Subtype C-

The second subtype is where the goal is not to build a path between our assumption and conclusion statements, but rather to show that it is impossible to build such a path, no matter how much we were to try.

This is not as easy as it might seem. If we only had a very limited toolbox of edges, we could somehow "try them all" in all possible combinations and show that the statements are impossible to connect. But when the toolbox of edges is potentially infinite, and even worse, when we cannot afford to restrict our claims to apply only to the edges that we already know... how could we ever be certain that it's impossible to connect them, and not that we've simply yet to learn the one edge that will solve all of our problems?

Well... What if we could build a path between the assumption statements and a statement that contradicts the conclusion statements? Or perhaps the other way around, between the conclusion statements and a statement that contradicts the assumption statements? Then it kinda works, right? Never mind that I've not defined what "contradicts" means, just vibe with it. Because if we can show that this path exists, then either the assumption or the conclusion statements cannot must not hold if the other does. Thus, there cannot be any paths. Or more accurately: were such a path to exist, our entire model of the world would lose consistency. And this cannot be allowed to happen.

You may notice that this technique also works for the Subtype C+: If we want to build a path between assumption and conclusion statements, we could show that it is possible to build a path between the opposite of the conclusion statement and a statement that contradicts the assumption statements. That also kinda works, right? Never mind that I've not defined what "opposite" means, just vibe with it. Since we know the assumption statements to be true, then the conclusion statements must also hold to avoid this contradiction.

So what?

If you're in any way like me, either you've just spent the last... I want to say 8 minutes... asking why I'm wasting your time stating the obvious, or further convincing yourself that I'm an idiot. Which is to say: Either what I've just described resonates strongly with what you call "thinking", or it doesn't.

The beauty for me is that, while I've used a couple of mathematical examples so far, this model can be applied to any other scenario where any kind of rational thinking is required. It should not be challenging to see how it can be used to express deductive reasoning, a Markov process, chemical synthesis and retrosynthetic analysis, and probably even more things that I can't think of right now or that I've not learned about yet.

And there's a couple more things that I'd like to talk about before wrapping things up.

Learning as hypergraph building

I said that the hypergraph does not exist, and that the thinking process is analogous to building this graph on the spot with a specific purpose. This would be a pure ab initio approach, and it's not the only approach possible. What if we already had some parts of our hypergraph pre-built?

Here is important to notice that not all statements are created equal. It makes no sense to pre-build a graph for evaluating mathematical expressions, because there are an infinite number of potential mathematical expressions to evaluate. But with more limited sets of statements, it might make sense. I'm sure you've memorized your multiplication tables, or some indefinite integrals that you could just as easily calculate integrating by parts.

Within the terms of this model, a first order approach to learning would be just memorizing new statements and adding new edges to our toolbox, to be used in the future when needed. Which we can distinguish from a second order approach to learning, where we aim to identify which parts of the hypergraph are worth building in advance, so that we can benefit from not having to reinvent the wheel on the spot every time. This is commonly achieved via repetition, rather than by pure memorization.

Keeping a consistent model of the world

Let's go back for a moment to that "contradicts" thing. No, I don't mean the fact that I've not defined it, you can look for definitions or just continue to vibe with it. I want to go back to what I said about the consistency of our model of the world. If you start to engage in what I've just called second order learning, you will start to build an ever-growing hypergraph that will be your companion for the rest of your life. This is your model of the world. It connects all the different things you've learned and ties them all together. This is, fundamentally, how smart you really are. You must protect it with your life, and there are two things that you cannot allow to happen.

The first one is obvious enough: you must avoid learning falsehoods. If you learn falsehoods, you will arrive to incorrect conclusions while believing to be correct. Even worse, if you let this go unnoticed second order learning will propagate this falsehood through your entire model of the world, poisoning it. This takes time to identify and fix, and I've written about it already.

The second one is a bit more tricky: you must avoid inconsistencies. Ultimately, this is a corollary of the previous one, since the reason inconsistencies arise is because of falsehoods. The reason I call it out separately is because of the nature of the falsehoods involved. Inconsistencies arise not due to outright falsehoods, but rather to subtle misconceptions on otherwise correct statements such as making incorrect generalizations. Also, inconsistencies are most likely to go unnoticed for a long time. While falsehoods will lead to incorrect conclusions immediately, an inconsistency will not be noticed until you learn a conflicting statement sometime later. And then you'll have a problem: You'll need to judge if the new statement that you're trying to add to your model of the world might be a falsehood, or if you need to reevaluate your model of the world because something in there cannot be quite true. You might not even notice the inconsistency and learn the conflicting statement without thinking twice about it, only to find yourself absolutely lost and confused when you try to use your model of the world at a later point in time.

This is for me the complete model of learning, that I might be tempted to call third order learning: You memorize new statements. You add new edges to your toolbox. You build your hypergraph in advance, and you keep going until you can be sure that the new statements are absolutely in agreement with the rest of your model of the world. If any conflicts are identified, you resolve them on the spot. I don't remember the exact example, but I do remember the situation (multiple, in fact) where I did not allow a professor to move forwards with their lecture because they've just delivered a statement that, were I to take it as-is, would introduce an inconsistency in my model of the world. I could not let that happen. If I did, it would mean that I'd effectively be leaving that class knowing less than when I came in. Come the fuck on.

By any other name

If we take another look at Type C thinking within a mathematical context, can you think of another name for it? You're trying to show, by applying a set of rules and principles, that you can use a given set of assumptions to guarantee a given conclusion. You're building a mathematical proof. And when we applied the technique used for Subtype C- on Subtype C+, that was proof by contradiction.

The observation here should be that building a mathematical proof is not a unique type of thinking. It's the same Type C thinking that you'd use when solving any other kind of problem. If you can write a proof, you can argue a case in front of a judge. You just gotta make sure your model of the legal world is good enough. You're missing the facts. But you're not missing the process.

Thinking about code

The final example I want to give of Type C thinking is how I think when writing code, and the reason why I love Haskell. I see writing code as trying to go from an initial set of types that codify my program's input to a final set of types that codify my program's output. The model of the world is made out of the different elements the programming language and its libraries give you to manipulate data and transform it or combine it from some given types into some other types. What in the context of logical thinking would be a hypothetical syllogism, we just call function composition.

All I have to do is find a path from my input types to my output types. If I can find this path, I solved the problem. And as with all Type C thinking, instinct plays a big role. Instinct will tell you that certain intermediate representations are likely to be useful. So I'll define those types as well. And instinct will also guide you in learning to identify the ways in which different types are or are not equivalent, and in the cases where they are not, what additional data is required to transform one into the other.

In a graph where the nodes are types are the edges are functions, I can use Type C thinking to write the entire skeleton of a program just at the type level, with a minimal implementation limited to glue code just to make sure all the pieces fit together but without any actual business logic. And if this type-checks, I'm almost certain that the code will just work once I implement it. Any errors past this point are usually me failing to properly understand the problem, and actually solving an entirely different problem.

I could show you how to put this into practice, but I believe that's better suited for a video than an article. For the moment, this will have to do. I've shared what I wanted to share. Now you think about it.

co

co